The children swayed back and forth to the train’s rhythm as it travelled through the countryside until it gradually slowed and came to a screeching halt.

Laura peered out the window at the vast emptiness of the land. Beyond the small station, there was nothing to see in any direction.

‘Do not get placed here, Johnny Miller. Ya hear me?’ She turned to look at the boy travelling with her, the boy she had known her entire life in the city.

‘It ain’t my choice. None of this is my choice.’ He looked around and then glanced down at his new trousers and shoes. Laura followed his gaze thinking, ‘Where were those shoes when he needed them? When he ran barefoot down the alleys?’ They were both dressed to impress in their new clothes to ensure a successful transition.

‘Play lame. They don’t want no dumb weakling.’

Johnny didn’t answer as the children exited the train to line up in size order. She pinched him angrily and hissed, ‘Play lame. Drool if you have to.’

The men appeared looking over the children like cattle, poking and prodding them, checking their scrawny arms for muscles. Only the fittest would be placed to work on the farms and given a home. The rest would board the train headed towards the next city for the process to begin again, with the selection shrinking at every stop.

Laura watched a man approach the line slowly while leaning on his cane. He stopped in front of Johnny and then flicked his cane up quickly striking the boy in the knee. ‘What’s your name, child?’

Holding her breath, she said a silent prayer for Johnny to keep his mouth shut as she had instructed him. He stood still, showing only the slightest hint of pain induced by the strike, and said nothing.

The man leaned in to study Johnny’s face. ‘You deaf or dumb?’

Receiving no response nor eye contact, the man abruptly turned to the next child and struck him with the cane. ‘How about you? You have a name?’

‘Albert.’

‘I’ll take him.’ Albert was roughly pulled off the line.

Laura, grateful for the absence of women, received hardly a glance in her direction. She stood staring at a point on the horizon letting her mouth droop open slightly.

‘All aboard!’ The harsh command signalled the transactions were complete.

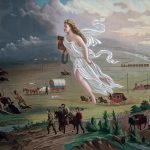

Once again, the rejected children boarded the orphan train heading west.

***

‘We ain’t no orphans, Laura. We both got a ma and pa back in the city.’

‘I know, Johnny. These folks are looking for farmhands, grabbing us up as if we don’t matter.’

‘My ma is going to worry when I don’t get home for supper.’

‘Your ma ain’t gonna notice, Johnny. She’s out looking to earn a few coins at the saloon. You know what she does when your pa is passed out drunk in the alley, don’t ya?’

Scowling, Johnny lashed out. ‘Take that back. Your ma is the one in the whorehouse.’

Laura recoiled at the words but knew the harsh statement was true. No one took care of them back home, making them easy targets for relocation.

***

The screeching woke Laura from her sleep, leaving her disoriented. After dreaming of the tiny apartment in the city, she was dismayed to find herself still on the train. She felt Johnny’s head on her shoulder and heard his gentle snoring.

After a quick glance out the window, her heart began to pound. She shoved her friend roughly.

‘Wake up, Johnny Miller.’

‘Watch it,’ the boy reacted quickly, his little hands going into fists ready for a fight.

‘Calm down. Behave yourself. We want to get placed here. It’s perfect for my plan.’

‘You ain’t the boss of me, Laura.’

‘You want to get back to New York? See your ma and pa? You best behave yourself. We have to stick together, or we’ll be lost forever. You want that?’

‘You know I don’t. Just stop being so damn bossy.’

‘Sorry,’ Laura whispered gently as they stepped off the train and looked around. Among the surrounding buildings was a general store with horses hitched to the posts out front. She knew what they had to do to survive.

‘This is it, Laura, ain’t it?’

‘Yes. Be fit, Johnny Miller. Be fit and get placed. Then get your sorry self to the store quickly. I’ll be there.’

‘You’re so sure of yourself?’

‘I am, Johnny Miller. I am.’

***

The children lined up in size order and were marched back and forth across the square. Laura quickly made eye contact with the women, looking for some favour. When approached, she recited her lines expertly, stating her name, age, and skill set. She added what she hoped would seal the deal.

‘I worked in my ma and pa’s shop back in New York. I can double your sales in a year. Mark my words.’

‘Aren’t you a bold little thing? Matilda, this lass is looking to take over the mercantile.’

‘She can have it along with the debt. Good luck to her.’ The woman scoffed.

‘I’m a hard worker. You won’t be sorry, ma’am.’

‘Why aren’t you back in the city working?’

‘My ma and pa were struck down with the flu, ma’am. Both dead and buried. I ain’t got no one,’ Laura’s chin quivered as a lone tear rolled down her cheek.

‘Can you read and write? Do math?’

‘Sure can. I was top of my class.’

‘You want her?’ The man turned to his wife who nodded.

***

‘Bag of flour.’

Laura’s heart raced as she looked up and smiled.

‘How’s it going, Johnny?’

‘They make me sleep in the barn.’

‘The barn? That’s disgraceful. You ain’t no animal.’

‘We’ll get home someday. I’ll be back on the corner selling newspapers instead of shovelling horse shit.’

‘And I’ll be eating pizza at Lombardi’s.’

‘You mean behind Lombardi’s digging through the garbage.’

‘No, I mean sitting inside eating properly with the kids.’

‘Kids?’

‘Yeah, Johnny. We’re gonna get married and have lots of babies.’

‘Married?’ Johnny took several steps backward, crashing into a rack of hard candies. ‘I ain’t marrying you!’

‘You got a better offer?’ Laura placed a bag of flour on the counter.

‘You ain’t the boss of me, Laura,’ he grumbled, putting down two coins for his purchase. Laura silently slid a pile across the counter, and after a quick nod, he put the cash into the pocket of his coveralls.

***

‘How long did it take you to get back to New York?’

‘Why all the questions, little one?’

‘It’s for my history paper. We’re learning about the orphan trains. I can’t believe you and Grandpa were on those.’

‘I’m surprised they are teaching you that in school.’

‘Why?’

‘We were the forgotten children. The unwanted, the downtrodden. No one cared about us.’

‘I’m sorry, Grandma.’

‘Don’t be sorry. We survived.’

The apartment door opened, and their attention turned to the elderly man carefully balancing two boxes.

‘Someone ordered pizza? Was that you, Laura Miller? Or you, little one?’ Johnny bent over to kiss his wife and then his granddaughter as they sat together at the kitchen table.