Edward Riggs White Surveyor General’s Office

Assistant Surveyor. Sydney. 28th March, 1849.

Sir,

To preserve the interests of the South Australia colony, I have the honour of appointing you to finish the duty of marking the line of boundary between the Port Phillip District of New South Wales and the Colony of South Australia. This duty is intended to be performed under the supervision of the Government, and you will be acting on the behalf of the South Australian Government, at the joint expense of both. You will take a small, assigned party to Wade’s marker at Lake Mundy, at which place I have stated to the Colonial Secretary of the latter Government you will in all probability have arrived by the beginning of August. You will be provided with food and camp equipage during your time of employment. Should problems arise in this duty, you will be in correspondence with Sir Robert Hoddle Esq. where your oversight of the survey will be communicated to the South Australian Government.

Your Obedient Servant.

T.L.Mitchell

Surveyor General.

November, 1849.

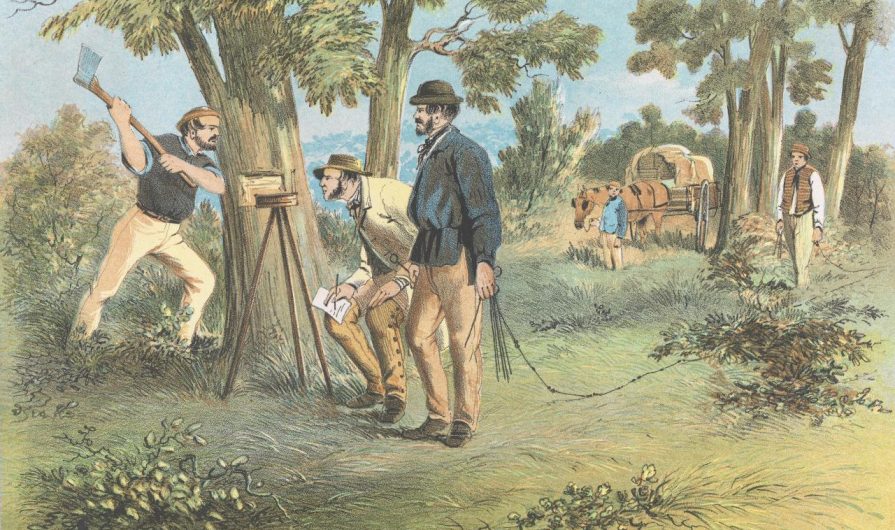

On Henry Wade’s attempt at marking the border between New South Wales and South Australia, the expedition had been hard. The supplies were low, but the manpower employed had been sufficient to rest. The days passed quickly then, the miles travelled with ease and precision. Wade’s decisions were made with authority and expertise that Edward Riggs White, one day, hopes to achieve.

In those final days at Lake Mundy before they went home, the water ran dry, horses collapsed, and men fled. Wade had made the decision to go no further.

Two years later in the same circumstances as Wade, White finds himself making a hard decision. He loads up two horses with supplies, leaving the bulk of the supplies at the camp with the remaining men. The months have been long and arduous, plagued by thin rations, dry riverbeds, and hot tempers. In the unwavering heat, men have quarrelled, stretched taut like the chains that creep them ever so slowly towards the river. They are on the final stretch, with the Murray looming ahead of them.

Despite knowing this, the mallee scrub seems to stretch on forever. The station nearby passes on a letter for assistance, but they don’t have the means to support the party.

This survey of the land has an end in sight, and White is not interested in attempting it a third time. He will go on alone, marking the points along the way until he reaches the safety of the river and then, once replenished, backtrack and complete the survey.

Under the heat of the sun, White heads out on his own, measuring chain after chain of the land, following the bearings given to him by Wade. He works as fast as he can, leaving markers along the track that will surely be hidden if rain or winds hit, but given the days of blue skies, he’s sure they will be standing upon his return.

As before, and as expected, the land proves difficult to traverse, with tough, dense scrub ahead of him. The rations deplete quickly, as well as his health. Six days into the journey, White is on his last legs.

Half a mile back, tethered to a bone-dry tree, his chestnut saddlehorse is dying of dehydration, the other horse, stumbling along under his hips, isn’t far off either. It’s been days of no food; the water rations— well exhausted by now.

The river is still ahead, two miles in a straight line through the semi-arid wasteland. Weariness all but consumes him. His tongue scrapes over his gums searching for moisture, the desert air in his nostrils feels like sand caressing over the dunes when the breeze picks up. The difference between life and death can be measured in two miles.

White’s horse stops walking and he urges her forward.

‘Two miles more, girl, you can do this,’ he rasps. They’ve been surveying this border for years; they can make it the final stretch.

‘Only two miles more,’ he says, speaking to himself more than anything.

When she stops again only a chain later, the likelihood of reaching the river by horseback reaches zero. Dismounting on shaky legs, the full force of the afternoon sun hits White, and light-headedness brings him to his knees. He lies down in the sandy dirt, regretting not steering them towards the shelter of the eucalypts that make up the mallee scrub. As if given permission, his horse collapses, the exertion too much to bear. She lifts her head, her big, pained eyes turned towards him once more, and then she dies.

The Murray River is still two miles away, his other dying horse is half a mile back. There’s no water and almost certain death if he goes back, but two miles ahead alone seems impossible.

White’s horse is still warm beside him, her blood coagulating more in her veins as the minutes go on. He needs water, he needs anything that will keep him alive. Laying alongside his horse in the sand, he makes his choice.

White cuts deep into her neck. Blood oozes out, black, thick and unhealthy-looking, having the same bad smell as his breath. He laps at it, forcing himself to swallow the slow trickling of liquid, managing half a pint of it before staggering to his feet once more. The sun beats down on him and the river is still two miles away.

He staggers onwards alone, with nothing but his compass and his empty water bladder. Marking the waypoints doesn’t feel important anymore, nor does the finishing of his assignment. To succeed now is to reach the Murray River, plunge himself face first into the water and drink like a horse in a trough.

Behind him, the scuffing of his feet mark the trail back to his dead horse, with divots in the dirt where he’s upended stones and roots. He beats his way through bushes without finesse, catching a few scratches to his ears along the way. Each stumbling step gets him closer to the end of this, and that thought, the one of finishing this survey once and for all, drives him forward. Forward, forward, forward.

White tumbles his way down the bank before he even registers that he’s made it, splashing down into the muddy edges of the Murray River. Standing tall on the banks of the river, the large gums block the glare from the afternoon sun, overhanging the pocket of paradise he’s found himself in. He crawls forward into the cool reprieve, swallowing mouthful after mouthful as he goes deeper, and lets the river consume him like the water itself could heal him.

Sitting between the edge of the two borders, after years of gruelling efforts, White’s assignment is finally complete. All that’s left to do is go back for his surviving, tethered horse.